Health Impact News Editor Comments: The science and history of the polio vaccine is written by Dr. Viera Scheibner . The entire article, History and Science Show Vaccines Do Not Prevent Disease, can be read here. This was extracted from her research presented in A critique of the 16-page Australian pro-vaccination booklet entitled “The Science of Immunisation: Questions and Answers” –You can read the entire report here.

While the polio vaccine is often referred to by those who believe in vaccines as the ultimate example of a vaccine that eradicated a terrible disease that is no longer with us, the science and history of this vaccine tell a vastly different story. From Dr. Scheibner’s research below, we can clearly see certain facts in the history of polio vaccination:

1. There has been more than one type of polio vaccine through its history, due to the fact that earlier versions were found to be ineffective and harmful.

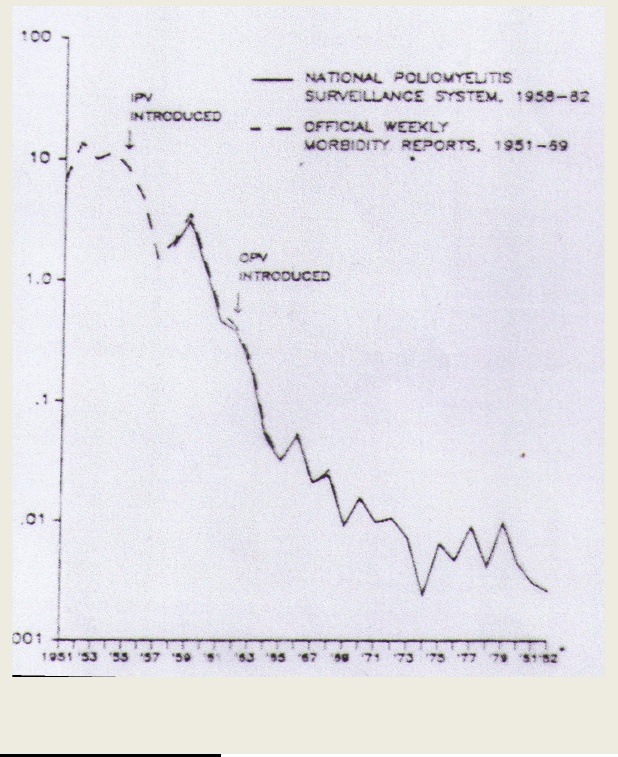

2. The occurrence of polio was trending downward prior to the introduction of polio vaccines.

3. The reported effectiveness accredited to polio vaccines can actually be easily accounted for by data manipulation and not actual decreases of occurrence. (See also Dr. Suzanne Humphries’ excellent treatment of this subject here: Did Vaccines Really Eradicate Polio?)

4. The history of the polio vaccine is a history of contamination of the vaccines responsible for the injury and deaths of countless people.

The sordid history of Poliomyelitis vaccination

By

Dr

. Viera

Scheibner

(PhD)

International Medical Council on Vaccination

When the Salk injectable “formaldehyde killed” polio vaccine was tested on some 1.8 million American children in 1954‐55, cases of paralysis in the vaccinated and some of their contacts started occurring within days.(43) The Cutter Laboratories were accused of distributing vaccines containing live polioviruses. Disasters with the Salk vaccines causing vaccine associated paralytic poliomyelitis (VAPP) seem to have been one of the main motivations behind development of an oral “live attenuated” Sabin vaccine, which was believed to simulate the natural infection. However, VAPP cases continued occurring with the Sabin vaccine.

I spent many hours locating and reading the older and more recent articles addressing the effectiveness, or otherwise, of combining IPV and OPV vaccines. I established that the results are not straightforward. Abraham reported that shedding of virulent poliovirus revertants, during immunization with oral poliovirus vaccines, after prior immunization with inactivated polio vaccines, continued.(44) He also documented that prior immunization with EIPV (enhanced potency IPV) does not prevent faecal shedding of revertant polioviruses after subsequent exposure to OPV. (45)

Mensi and Pregliasco wrote:

In recent years great alarm has been generated by outbreaks of paralytic poliomyelitis in vaccinated populations…epidemics were observed in Finland in 1984, Senegal and Brazil in 1986, and Israel and Oman in 1988, all countries in which vaccination is widely deployed. Four epidemics were reported between 1991 and 1992. The first, in 1991, was in Bulgaria, which uses oral vaccination. Forty-three subjects developed paralytic type 1 polio; 88% of them belonged to a normal community and had not completed or even started a vaccination schedule. The second epidemic occurred in The Netherlands, where inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) is used, and involved 68 patients with type 3 poliovirus, members of the Amish…(46) [In The Netherlands they are called members of orthodox religion and in fact use the polio vaccination (compliance between 40‐50% and higher)].

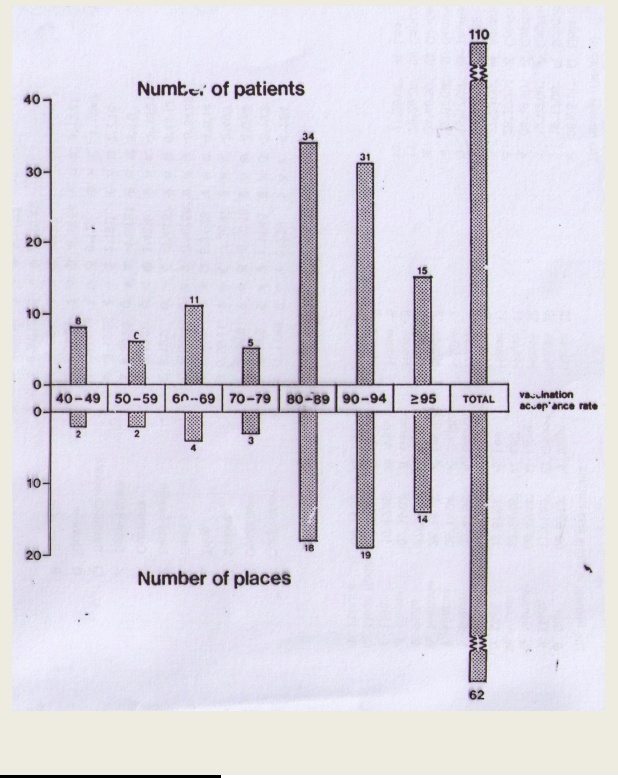

Schaap et al. published a graph (figure 14) correlating the number of reported poliomyelitis cases with the vaccination rates in seven areas in The Netherlands.(47) Interestingly, the areas with the lowest compliance had the lowest number of cases and vice versa. The compliance ranged from 40‐49% to 90‐95%. In the 1992 epidemic, the first two cases occurred in a 14‐year old boy and 23‐year old male nurse, both vaccinated members of the orthodox religious group.

Sutter et al described an Oman outbreak as:

. . . evidence for widespread transmission among fully vaccinated children.(48)

Incidence of paralytic disease was highest in children below 2 years:

. . . despite an immunisation programme that recently had raised coverage with 3 doses of oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) among 12-months-old children from 67% to 87%… with transmission lasting for more than 12 months. Among the most disturbing features of this outbreak was that it occurred in the face of a model immunisation programme and that widespread transmission had occurred in a sparsely populated, predominantly rural setting. (49)

One of the interesting reasons quoted was:

. . . rapid increases in vaccination coverage before the outbreak may have reduced or interrupted endemic circulation of indigenous strains, diminishing the contribution of natural infection to overall immunity levels in the general population. (50)

The same reason was given by Biellik et al. in 1994 when they described the situation in Namibia. They wrote:

Endemic wild poliovirus circulation has continued uninterrupted in Angola and the two northern regions in Namibia across the well-travelled border since 1989, when cases were last reported. Although OPV3 cover age was fairly low in northern compared with southern Namibia, a higher proportion of northern children might have been protected, at least to type 1, by natural immunity, thus suppressing epidemics . . . the apparent interruption of [natural] poliovirus circulation [by vaccination] limited the acquisition of natural immunity. (5)1

Control of polio in the US shows the same phenomenon as the control of pertussis, namely downward trend, which stopped when individual states in the US mandated DPT and polio.

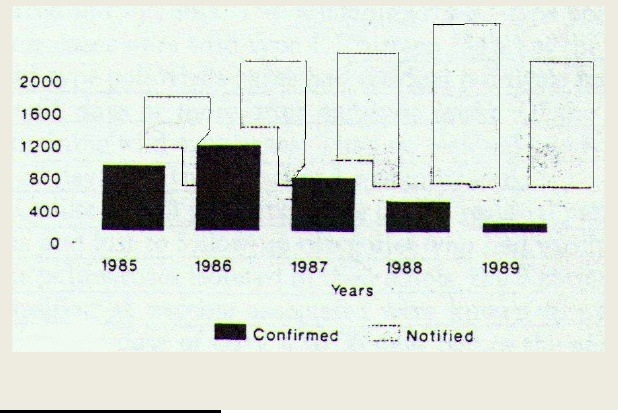

An interesting example of manipulation of data is polio “eradication” in the Americas. Figure 16(52) shows the effect of reclassification of poliomyelitis which allowed the ever increasing number of “notified” cases to morph into an ever decreasing number of “confirmed” cases.

Dr HV Wyatt (53) quoted Hanlon et al. as stating:

…injections during an epidemic may provoke poliomyelitis in children already infected with poliovirus, [and] …provocation poliomyelitis occurs with injections of diphtheria/pertussis/tetanus vaccine, which, I am told, gives rise to unease among vaccinators. The risk of provocation poliomyelitis with the killed poliovaccine…occurred in the Cutter incident.

During a poliomyelitis outbreak in Taiwan, Kim et al. reported that 65% of VAPP developed within 28 days of the first vaccine dose This report confirmed observations of others that two thirds of vaccine‐targeted diseases occur after the first dose of relevant vaccines, including the polio vaccine,(54) and it also unwittingly confirmed the original and true definition of herd immunity that has nothing to do with vaccines: Epidemics occur during the accumulation of two thirds of susceptibles. Once natural immunity is 2/3 of susceptibles get the disease, the epidemic stops. Yet, the authors excluded (as unvaccinated) all paralytic cases (65% of all cases) from calculations of efficacy. Ogra evaluated vaccination with live attenuated and inactivated poliovirus vaccines:

While the combination schedule employing EP-IPV followed by OPV should result in a decline of vaccine-associated (VAP) decease in OPV recipients, such immunization schedule may have little or no impact on the development of VAP in susceptible contacts. Furthermore, the logistics and the cost of combination schedule must be considered before current recommendations based on the use of OPV or EP-IPV alone are revised.(55)

Combined OPV and IPV recommendations

Continuing failures of polio eradication by OPV led to the proposals of using a combination of killed followed by oral polio vaccine delivery. However, such proposals are flawed and based on the ignorance of the documented past experience.

Simian Virus 40 contamination of polio vaccines

Perhaps the worst thing about polio vaccines is their continued contamination by monkey viruses of which SV 40 is the best researched one. According to ample medical research evidence, polio vaccines of any kind cause VAPP. However, there are other major problems with the polio vaccine that justify scepticism about its benefits, one of which is the well‐documented and continuous contamination by monkey viruses SV1‐SV40. Soon after the poliovirus mass vaccination programmes started in the US, a number of monkey viruses and amoebas were found in the vaccine seed brews. Hull, Milner et al. (56) and Hull, Johnston et al. (1955) encountered numerous filterable, transferable cytopathogenic agents other than polio virus in “normal” monkey renal cell cultures. Even though these agents completely destroyed culture tissues, and even caused serious diarrhoea in laboratory animals, all of which died, their possible pathogenesis in humans was ignored or glossed over. The central nervous system was particularly susceptible to the pathogenic properties of such viruses; the histopathological lesions observed in the intracerebrally inoculated monkeys revealed necrosis and complete destruction of the choroid plexus. Findings included generalised aseptic type meningitis. The isolated agent was called simian virus or SV and classified into 4 groups based on the cytopathogenic changes induced in monkey kidney cell cultures infected with these agents.

Hilleman and Sweet (57) reported on the “Vacuolating virus S.V. 40”, which became the best researched among dozens of known monkey viruses. Gerber et al. (58) demonstrated that Sweet and Hilleman’s method of inactivation of SV40 by 10 day treatment using 1: 4000 solution of formaldehyde was inadequate, since it took longer than 10 days to establish that the process was a subject to the asymptotic factor and hence incomplete. Fenner’s research (59) has also established that even the inactivated portion of the viruses reverts back to the original virulence. Dr Bernice Eddy documented the carcinogenic properties of these simian viruses: they caused tumours in hamsters injected with Rhesus monkey kidney cell extracts. (60) As established by many subsequent researchers, in humans SV40 causes characteristic brain tumours, bone sarcomas, mesotheliomas and an especially virulent form of melanoma cancer. The stage was ready for a world‐wide [admitted] contamination of hundreds of millions of children with an oncogenic monkey virus via polio vaccines. SV40 has been directly or indirectly implicated in an epidemic of great number of conditions and brain, lung, bone, renal and other tumours in all ages. (61,62,63,64,65)

Dr Stanley Kops is a modern day advocate for SV40 truth, and he wrote:

To date, the scientific literature and research examining SV40 and cancer-related diseases has been based upon an assumption that SV40 was not present in any poliovirus vaccines administered in the United States and was removed from the killed polio vaccines by 1963. The presumption has been that the regulation for live oral polio vaccine required that SV40 be removed from the seeds and monovalent pools ultimately produced in the manufacturing process…The confirmation of the removal by one manufacturer, Lederle, has been made public at an international symposium in January 1997, where its representatives stated that all Lederle’s seeds had been tested and screened to assure that it was free from SV40 virus. However, in litigation involving the Lederle oral polio vaccine, the manufacturer’s internal documents failed to reveal such removal in all its seeds. The absence of confirmatory testing of the seeds, as well as testimony for SV40 of a Lederle manager indicate that this claim cannot be fully substantiated…(66)

The scientific community should not be content with assurances to the contrary. The continuing occurrence of the above characteristic SV40 tumours in younger and especially quite recent generations of vaccinees should not be ignored or treated with indifference.

Contamination of polio vaccines by chimpanzee coryza virus, or RSV.

Another important consideration in attempts to eradicate poliomyelitis by vaccination is the contamination of polio vaccines by chimpanzee coryza virus, renamed respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

In 1956, Morris et al. described monkey cytopathogenic agent that produced acute respiratory illness in chimpanzees at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and named it chimpanzee coryza virus (CCA). (67)

In 1957, Chanock et al. wrote on the association of a new type of cytopathogic myxovirus with infantile croup. (68)

Chanock and Finberg reported on two isolations of similar agents from infants with severe lower respiratory illness (bronchopneumonia, bronchiolitis and laryngotracheobronchitis). The two viruses were indistinguishable from an agent associated with the outbreak of coryza in chimpanzees (CCA virus) studied by Morris in 1956.

A person working with the infected chimpanzees subsequently experienced respiratory infection with a rise in CCA antibodies during convalescence. They proposed a new name for this agent “respiratory syncytial virus” (RSV). RSV has spread via contaminated polio vaccines like wildfire all over the world and continues causing serious lower respiratory tract infections in infants.

Beem et al. isolated the virus from inpatients and outpatients in the Bob Robert Memorial Hospital for Children (University of Chicago) during the winter of 1958‐1959, in association with human acute respiratory illness. (69) The virus (named Randall) had an unusual cytopathic effect characterised by extensive syncytial areas and giant cells. Soon, 48 similar agents were isolated from 41 patients. There were antigenic similarities between RV and Long and Sue strains of CCA; it produced illness in humans (the age range 3 weeks to 35 years): acute respiratory diseases, croup, bronchiolitis, pneumonia and asthma ranging from mild coryza to fatal bronchiolitis. The isolation rate (46%) was particularly high among infants below six months.

In Australia, Lewis et al. isolated further viral specimens identical with CCA. (70)

Prior to July 1960, the influenza and parainfluenza viruses predominated in infant epidemic respiratory infections; in July 1961 the pattern changed abruptly with sudden increases in bronchiolitis and bronchitis, that were previously infrequent. 58% were under 12 months, and patients under 4 years predominated. Infants with bronchiolitis and severe bronchitis yielded RCA, not previously isolated. Deaths have occurred.

Rogers’ 1959 observations on antibiotic ineffectiveness, and new serious additional problems fell on deaf ears. He wrote that life‐threatening microbial infections continued to occur despite antibiotics, and that the previous microbial landscape also shifted by 1957‐1958. There was streptococcal predominance from 1938‐1940, and then an “impressive” increase in the number of life‐threatening enterobacterial infections post antibiotic.

During the preantimicrobial era most infections were acquired before admission to hospital, while in the postantimicrobial era the vast majority of infections arose in hospital . . . Mycotic infections, especially with Candida albicans, became a major problem. Unusual serious generalised clostridial infections arose and antibiotics have not dramatically altered the risk of, or mortality resulting from, endogenous infections in sick, hospitalised patients. (71)

Levy et al. wrote:

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the most prevalent cause of lower respiratory tract infections (LRTI) in infants and young children. Infections with RSV is a major health problem during early childhood and primary RSV infections occurs most often between the ages of 6 weeks and 2 years. Approximately one half of all infants become infected with RSV during the first year of life and nearly all infants by the end of their second year of life…in the US each year, approximately 100,000 children are hospitalised at an estimated cost of $300 million. More than half of those admitted for RSV bronchiolitis are between 1 and 3 months of age. (72) [Clearly implicating vaccination.]

RSV vaccine developed in the late 1960s failed miserably. It is no mystery why there is no RSV vaccine recommended today. Fulginiti and others showed the vaccine was ineffective, and induced an exaggerated, altered clinical response… causing RSV illness requiring hospitalisations among vaccinees, and led to delayed dermal hypersensitivity. (73)

Simoes wrote:

Since it was identified as the agent that causes chimpanzee coryza in 1956, and after its subsequent isolation from children with pulmonary disease in Baltimore, USA, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) had been described as the single most important virus causing acute respiratory-tract infections in children. The WHO estimates that of the 12.2. million annual deaths in children under 5 years, a third are due to acute infections of the lower respiratory tract. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and RSV are the predominant pathogens… vaccinated children were not protected from subsequent RSV infection. Furthermore, RSV-naïve infants who received formalin-inactivated RSV vaccine, and who were naturally infected with RSV later, developed more severe disease in the lower respiratory tract than a control group immunized with a trivalent parainfluenza vaccine. (74)

It should surprise nobody that data from ten developing countries – with intense polio vaccination, revealed that RSV was the most frequent cause of LRT infections (70% of all cases).

Polio vaccines are not only ineffective in preventing paralysis, they carry the risk of contamination with many harmful adventitious microorganisms, of which only some monkey viruses have been researched in more detail. Many other potentially dangerous microorganisms remain unaddressed.

Polio vaccination and brain-eating amoebas.

Contamination of monkey kidney tissue cultures (used in the production of polio vaccines) by live amoebas.

In 1996, while watching a TV news report on the death of two 5‐year olds in Australia from brain‐eating amoebae, I remembered a note in Hull et al.’s paper

Recently, an amoeba was isolated from monkey kidney tissue cultures and was identified as belonging to the genus Acanthamoeba. It grew readily in tissue cultures… It appeared to have the ability to infect and kill monkeys and mice following intracerebral and intraspinal inoculation.(75)

Amoebas are unicellular protozoan microorganisms. According to Ma et al.(76), they are classified in the phyllum Sarcomastigophora and belong to Rhizopoda, equipped by propulsive pseudopodia and/or protoplasmic flow without production of pseudopodia. Acanthopodina, a suborder of Amoebida, form two families, Vahlkampfiidae and Acanthoamoebididae, with two genera Naegleria and Acanthamoeba respectively, with a number of species. Naegleria species form three life‐stages, trophozoites, flagellates and cysts and Acanthamoeba species only two, trophozoites and cysts.

Jahnes et al.(77) isolated two strains of apparently the same amoeba which looked like round bodies, similar in appearance to cells manifesting changes induced by certain simian (monkey) viruses. On closer examination, they proved to be amoebic cysts. They varied in size, from 10 to 21 microns in diameter. In one experiment, the cysts were treated with 10% formalin, washed and inoculated into monkey kidney tissue culture tubes. The monkey kidney cells phagocytised the cysts. The trophozooites turned into cysts under refrigeration down to 4 degrees C. These were resistant even under –50 degrees C for months and survived in the pH range 5.0‐9.0. Their tissue cultures were not affected by streptomycin and penicillin.

Culbertson (78,79) confirmed that amoebas caused brain disease and death within days, in monkeys and mice. The reports showed, that following inoculations, “extensive chorio‐meningitis and destructive encephalomyelitis occurred” and killed monkeys in four to seven days and mice in three to four days. Intravenous injections of the amoebas resulted in perivascular granulomatous lesions. Intranasal inoculation in mice resulted in fatal infections in about four days. These mice exhibited ulceration of the frontal lobes of the brain. There were amoebas in the lungs, and they caused severe pneumonic amoeba reaction. Haemorrhage was a common feature. Sections of the kidney showed amoebas present in the glomerular capillaries.

Amoebas showed the ability to migrate through the tissues. The size of the inoculum did not matter: both small and large inoculums produced amoebic invasions. Intragastric inoculations were unsuccessful most probably because amoebic cysts were dissolved by bile.

Researchers, as a rule failed to address the seriousness of the introduction into children of Acanthamoeba via the polio vaccines, even though they were aware of their origin from monkey kidney tissue cultures used in the production of polio vaccines. However they noted that the most contaminated age group was babies below the age of crawling – between 2 and ten months.

Live amoebas were isolated from the air (80) in the UK, together with respiratory syncytial virus, and from the surfaces in hospital cubicles in which infants with acute bronchiolitis were being nursed. The amoebas were isolated at Booth Hall Children’s Hospital in the cubicle occupied by a ten‐week‐old infant with acute bronchiolitis. First, only RSV was isolated and the child sent home, but later an unidentified cytopathic effect was noticed in the tissue cultures and was provisionally called “Ryan virus1” (81) by Pereira, and later also noted in a post‐mortem bronchial swab of another seven‐months old baby boy with RSV bronchiolitis.

Pereira’s paper describes the course of illness: Six days before admission, the baby developed a sore throat and ulcers in the mouth which later spread over the face; he was unwell, could not suck and developed loose stools. The day before admission, he developed a cough and started vomiting. He was drowsy and dyspnoeic, made jerky movements and died soon after admission. Necropsy showed some emphysema, petechiae, and small areas of congestion and alveolar haemorrhaging in the lungs, a fatty liver, prominent mesenteric nodes, and mucopus in the ears. Escherichia coli bacteria were cultured from his ears. Death was diagnosed as due to a respiratory infection associated with encephalomyelitis and hepatitis. Vaccination status was not disclosed, although considering the age, the baby could have received up to three doses of DPT and OPV vaccines.

Armstrong and Pereira identified the Ryan virus as Hartmanella castellanii. (82) They had no doubt that these amoebas came from the human respiratory tract. In Australia, Fowler and Carter(83) Carter(84), and Carter et al.(85) described a number of cases in children and adults. Many cases all over the world occurred in children and adults, with and without histories of swimming in lakes and public swimming pools. (86)

Even if polio vaccines were effective in preventing polio paralysis, their potentially continued contamination by undesirable microorganisms (monkey viruses and amoebas) should encourage the abandonment of their use.

Well‐meaning Rotarians should study the relevant medical research first, before engaging in global polio vaccination.

The entire article, History and Science Show Vaccines Do Not Prevent Disease, can be read here.

Extracted from: A critique of the 16-page Australian pro-vaccination booklet entitled “The Science of Immunisation: Questions and Answers” –You can read the entire report here.

Vaccine Epidemic

by Louise Kuo Habakus and Mary Holland J.D.

FREE Shipping Available!

References

43 Peterson et al. VACCINATION-INDUCED POLIOMYELITIS IN IDAHO: PRELIMINARYREPORT OF EXPERIENCE WITH SALK POLIOMYELITIS VACCINE. JAMA. 1955;159(4):241-244

44 Abraham R, Minor P, Dunn G, Modlin JF, Ogra PL. Shedding of virulent poliovirus revertantsduring immunization with oral poliovirus vaccine after prior immunization with inactivated poliovaccine.J Infect Dis. 1993 Nov;168(5):1105-9.

45 Carolina Mensi and Fabrizio Pregliasco. Poliomyelitis: Present Epidemiological Situation andVaccination Problems. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998 May; 5(3): 278–280.

46 Mensi C, Pregliasco F. Poliomyelitis: present epidemiological situation and vaccination problems.. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998 May;5(3):278-80.

47 Schaap GJ, Bijkerk H, Coutinho RA, Kapsenberg JG, van Wezel AL. The spread of wild poliovirusin the well-vaccinated Netherlands in connection with the 1978 epidemic. Prog Med Virol.1984;29:124–140

48 Sutter RW, Patriarca PA, Brogan S, Malankar PG, Pallansch MA et al. Evidence for widespreadtransmission among fully vaccinated children Lancet. 1991 Sep 21;338(8769):715-20

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid.

51 Biellik RJ, Lobanov A, Heath K, Reichler M, Tjapepua V et al. Poliomyelitis in Namibia. Lancet.1994 Dec 24-31;344(8939-8940):1776

52 De Quadros CA, Andrus JK, Olivé JM, Da Silveira CM, Eikhof RM et al. Eradication of poliomyelitis: progress in the Americas. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991 Mar;10(3):222-9.

53 Wyatt HV. Poliovaccination in the Gambia. Lancet. 1987 Jul 4;2(8549):43.

54 Kim-Farley RJ, Rutherford G, Lichfield P, Hsu ST, Orenstein WA, Schonberger LB, Bart KJ, LuiKJ, Lin CC. Outbreak of paralytic poliomyelitis, Taiwan. Lancet. 1984 Dec 8;2(8415):1322–1324.

55 Ogra PL. Comparative evaluation of immunization with live attenuated and inactivated poliovirusvaccines.Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995 May 31;754:97-107.

56 HULL RN, MINNER JR, SMITH JW. New viral agents recovered from tissue cultures of monkeykidney cells. 1956. Am J Hyg;63:204-215.

57 Sweet, B. H., and M. R. Hilleman. The vacuolating virus, SV40. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1960 Nov;105:420-7.

58 GERBER P, HOTTLE GA, GRUBBS RE. Inactivation of vacuolating virus (SV40) byformaldehyde. Proc Soc Exp Biol and Med; 108: 205-209.

59 Fenner F. Reactivation of Animal Viruses. Br Med J. 1962 July 21; 2(5298): 135–142.

60 EDDY BE, BORMAN GS, BERKELEY WH, YOUNG RD. Tumors induced in hamsters byinjection of Rhesus monkey kidney cell extracts. 1961. Proc Soc Exp Biol and Med; 107; 191-7.

61 Carbone M, Pass HI, Rizzo P, Marinetti M, Di Muzio M et al. Simian virus 40-like DNA sequencesin human pleural mesothelioma. Oncogene. 1994 Jun;9(6):1781-90.

62 Bergsagel DJ, Finegold MJ, Butel JS, Kupsky WJ, Garcea RL.DNA sequences similar to those of simian virus 40 in ependymomas and choroid plexus tumors of childhood. N Engl J Med. 1992 Apr 9;326(15):988-93.

63 Carbone M, Rizzo P, Grimley PM, Procopio A, Mew DJ Simian virus-40 large-T antigen binds p53in human mesotheliomas. Nat Med. 1997 Aug;3(8):908-12.

64 Butel JS and Lednicky JA. Cell and molecular biology of simian virus 40: implications for humaninfections and disease.J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999 Jan 20;91(2):119-34.

65 Weiner LP, Herndon RM, Narayan O, Johnson RT, Shah K Isolation of virus related to SV40 from patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. 1972. NEJM;286(8):385-390.

66 Kops, SP. Oral polio vaccine and human cancer: a reassessment of SV40 as a contaminant basedupon legal documents. Anticancer Res. 2000 Nov-Dec;20(6C):4745-9.

67 Blount, R. E., Jr., J. A. Morris, and R. E. Savage. 1956. Recovery of cytopathogenic agent fromchimpanzees with coryza. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 92:544-549.

68 CHANOCK R, FINBERG L. Recovery from infants with respiratory illness of a virus related tochimpanzee coryza agent (CCA). II. Epidemiologic aspects of infection in infants and young children.Am J Hyg. 1957 Nov;66(3):291-300

69 BEEM M, WRIGHT FH, HAMRE D, EGERER R, OEHME M. Association of the chimpanzeecoryza agent with acute respiratory disease in children. N Engl J Med. 1960 Sep 15;263:523-30.

70 Lewis et al.. A syncytial virus associated with epidemic disease of the lower respiratory tract ininfants and young children. 1961. Med J Australia: 932-933 and Forbes (1961. Ibid: 323-325).

71 ROGERS DE. The changing pattern of life-threatening microbial disease. N Engl J Med. 1959 Oct1;261:677-83.

72 Levy BT, Graber MA. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in infants and young children.J Fam Pract. 1997 Dec;45(6):473-81.

73 Fulginiti VA, Eller JJ, Sieber OF, Joyner JW, Minamitani M et al. Respiratory virus immunization. I.A field trial of two inactivated respiratory virus vaccines; an aqueous trivalent parainfluenza virusvaccine and an alum-precipitated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine.Am J Epidemiol. 1969Apr;89(4):435-48.

74 Simoes EA. Respiratory syncytial virus infection.Lancet. 1999 Sep 4;354(9181):847-52.

75 Ibid Hull 1958.

76 Ma P, Visvesvara GS, Martinez AJ, Theodore FH, Daggett PM et al. Naegleria and Acanthamoebainfections: review. Rev Infect Dis. 1990 May-Jun;12(3):490-513.

77 JAHNES WG, FULLMER HM. Free living amoebae as contaminants in monkey kidney tissueculture. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1957 Nov;96(2):484-8.

78 CULBERTSON CG, SMITH JW, MINNER JR. Acanthamoeba: observations on animal pathogenicity. Science. 1958 Jun 27;127(3313):1506.

79 CULBERTSON CG, SMITH JW, COHEN HK, MINNER JR. Experimental infection of mice andmonkeys by Acanthamoeba. Am J Pathol. 1959 Jan-Feb;35(1):185-97.

80 D. Kingston and D. C. Warhurst.. Isolation Of Amoebae From The Air J Med Microbiol February 1969 vol. 2 no. 1 27-36.

81 Pereira MS, Marsden HB, Corbitt G, Tobin JO. Ryan virus: a possible new human pathogen.Br Med J. 1966 Jan 15;1(5480):130-2.

82 J. A. Armstrong and M. S. Pereira. Identification of “Ryan Virus” as an amoeba of the genusHartmannella. Br Med J. 1967 January 28; 1(5534): 212–214.

83 M. Fowler and R. F. Carter.Acute Pyogenic Meningitis Probably Due to Acanthamoeba sp.: aPreliminary Report. Br Med J. 1965 September 25; 2(5464): 734-2, 740-742.

84 Carter RF. Primary amoebic meningo-encephalitis: clinical, pathological and epidemiologicalfeatures of six fatal cases. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1968 Jul;96(1):1–25.

85 Carter RF, Cullity GJ, Ojeda VJ, Silberstein P, Willaert E. A fatal case of meningoencephalitis dueto a free-living amoeba of uncertain identity–probably acanthamoeba sp.Pathology. 1981 Jan;13(1):51-68.

86 Scheibner 1999. Brain-eating bugs: the vaccine connection. Nexus Magazine;(whale.to/vaccines/amoebas.html).