Protest Dengvaxia (Bullit Marquez, AP)

Sanofi Dengue Vaccine: Dengvaxia Poses Serious Risk for Children

by Alliance for Human Research Protection

This is a developing news story focusing on the corruption of industry-initiated government vaccination policies. The case involves Sanofi and the launching of its Dengvaxia vaccine in a massive school-based Dengvaxia vaccination campaign in 830,000 Filipino school children.

The New York Times has just published its report, ![]() noting that:

noting that:

“public health experts are worried that the distrust could spill over to other vaccination programs.”

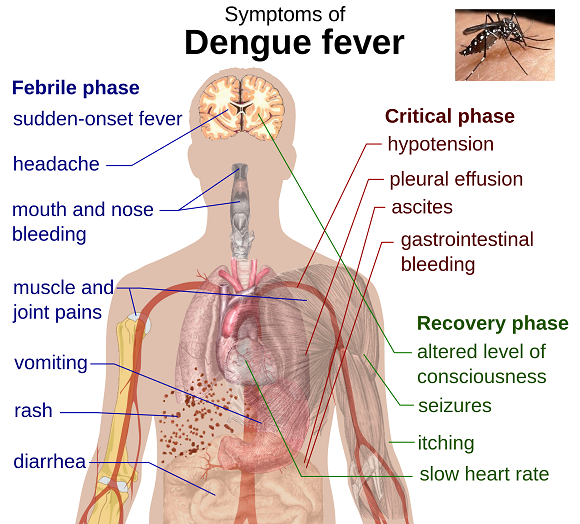

“The illness, also called breakbone fever, can be excruciating, with high fevers, headaches, muscle and joint pains and lingering weakness. Sometimes the disease causes hemorrhage or shock, which can be fatal…

Research has found that severe illness can occur in people who had one [of four dengue viruses] and later became infected by another. The body’s immune response to the first virus is thought to make the second illness worse.”

Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease expert at Vanderbilt University, is quoted stating:

“Vaccines have plenty of controversy. We don’t need to make more.”(NYT)

The World Health Organization reports that dengue, a virus transmitted by mosquitoes, is endemic in 100 countries, and the number of reported dengue cases has skyrocketed. In 1996, less than half a million (0.4); in 2005, 1.3 million; in 2010, 2.2 million; and in 2015, there were 3.2 million reported cases.

Sanofi Pasteur tested its vaccine Dengvaxia (CYD-TDV) in two parallel Phase 3 randomized trials (June 2011 – March 2012). CYD14 was tested in 5 Asian countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam), in 10,275 children aged 2–14 years. CYD15 was conducted at in 5 Latin American countries (Brazil, Colombia, Honduras, Mexico, and Puerto Rico, in 20,869 children aged 9–16 years.

But Sanofi failed to examine the reason that young children aged 2 to 5 were at increased risk of severe dengue infection; the company encouraged the Philippine government to initiate a massive, school-based Dengvaxia vaccination program. One year after 830,000 children in the Philippines were vaccinated, and a major scandal erupted in the Philippines, the World Health Organization changed its initial equivocating recommendation (by the same Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety) regarding Sanofi’s dengue vaccine, Dengvaxia:

“Dengvaxia prevents disease in the majority of vaccine recipients but it should not be administered to people who have not previously been infected with dengue virus.”

Sanofi’s 2015 report of Latin American trial published in The New England Journal of Medicine[1] stated:

“Overall efficacy against any symptomatic dengue disease was 60.8 percent* in children and adolescents 9-16 years old who received three doses of the vaccine. Analyses show a 95.5 percent* protection against severe dengue and an 80.3 percent* reduction in the risk of hospitalization during the study.

The results of this second phase III efficacy study confirm the high efficacy against severe dengue and the reduction in hospitalization observed during the 25-month active surveillance period of the first phase III efficacy study conducted in Asia, highlighting the consistency of the results across the world.”

Sanofi’s report of the Asian Dengvaxia trial was published in the journal Vaccine [2] (2015) also stressed the positive:

“consistent safety and efficacy…good safety profile. Secondary analyses also showed efficacy against all four dengue serotypes and protection against severe disease and hospitalization”…

the development of a dengue vaccine, similar to other recent vaccine successes against human papillomavirus and pneumococcal disease, requires a long standing and continuous effort from private and public organizations. In this regard, we have in the past 22 years benefited from multiple external collaborations across five continents.”

However, an increased risk of dengue infection was noted:

“risk of hospitalization for virologically confirmed dengue in the vaccine group as compared with the control group…the risk was observed in younger children, particularly the youngest age group, 2-5 years.”

- This was a red flag: rather than preventing dengue, for some populations, Dengvaxia increased the risk of severe, life-threatening dengue infection.[3]

- But Sanofi scientists failed to fully examine the potential risks described in published reports;

- Sanofi failed to consider how previous dengue infection can influence the response to the vaccine;

- Sanofi failed to appreciate how previous exposure – or non-exposure – determines the long-term, potentially deadly outcome.[4] [5]

- Sanofi ignored the cautionary advice of Dr. Scott Halstead, a widely recognized leading scientist in dengue research whose numerous papers in journals discussed the specific immune response problem posed by four different dengue viruses.[6]

Dr. Halstead wrote to the WHO urging that they proceed cautiously when rolling out the dengue vaccine. He had warned about the unique problems posed by a dengue vaccine, specifically re-exposure to dengue virus increases the risk of a potentially lethal complication when a person is infected a second time; it can result in hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome – which can lead to organ failure and death. The process is known as antibody-dependent enhancement or ADE. In an interview with Reuters, he stated: “It was not obvious to Sanofi and the World Health Organization, but it was obvious to me.”2

Indeed, the WHO issued an equivocating position paper in July 2016:

“The findings [of increased risk] in children aged 2–5 years are unlikely to be due to chance. In the younger age groups, the vaccine may act as a silent natural infection that primes seronegative vaccines to experience a secondary-like infection upon their first exposure to dengue virus. Vaccination may be ineffective or may, theoretically, even increase the future risk of severe dengue illnessin those who are seronegative at the time of first vaccination regardless of age.

If this is the case, even in high transmission settings there may be[an] increased risk among seronegative persons despite a reduction in dengue illness at the population level.”

Given that few (if any) of the countries involved have sophisticated screening programs in place to measure seroprevalence, the WHO recommendation is irrelevant:

“The vaccine is not recommended when seroprevalence is below 50% in the age group targeted for vaccination.”

The following statement in the same WHO document – within the context of an acknowledgment of the severe risk posed by CYD-TDV vaccine – is mind-boggling:

“Co-administration studies previously conducted in children outside the indicated age range, in which CYD-TDV was co-administered with YF vaccine, DTaP-IPV/Hib, and MMR, did not identify any safety concerns (data were comparable when vaccines were co-administered or given alone), and that the immunogenicity profiles were satisfactory both for CYD-TDV and for co-administered vaccines… Clinical trials are planned to assess safety and immunogenicity with human papillomavirus (HPV) and tetanus toxoid and reduced-dose diphtheria (TdaP) vaccines in endemic settings.”

The Philippine government under the Benigno Aquino regime initiated a massive school-based Dengvaxia vaccination drive in January 2016, subjecting more than 830,000 children to the severe risks posed by the vaccine. Sanofi and the former Philippines’ Secretary of Health, Janette Garin ignored scientists who warned about the potentially deadly risk. More than likely, company executives had their eyes fixed on the potential $1 billion annual sales of Dengvaxia.[7] Sanofi launched the vaccine in 11 countries in 2016.

Several investigations are underway, including a criminal probe, to determine whether Philippine officials who launched this devastating vaccination drive were corrupt. GMA News reported that Susan Mercado, a former undersecretary of the Department of Health stated that the government’s purchase of Dengvaxia for 3.5 billion pesos ($69 million) had not gone through the required approval process:

“the P3.5-billion Dengvaxia deal and the actual administration of the vaccine during the administration of President Benigno Aquino III was a scam because it did not go through the required government processes.” (Dec. 6, 2017)

Dr. Garin claimed that the Health Department was unaware that Sanofi withheld information about the vaccine prior to the approval of the 3.4 billion pesos deal. She defended the vaccination campaign, stating “it was an institutional decision to address a public need.” The actual purchase, she said, was made by Philippine Children’s Medical Center (PCMC) after consultation with “medical experts and medical professionals about the vaccine.”

Reuters reports [8] that its review of internal DOH documents show that Garin disregarded expert scientists concerns about the possibility of causing harm; and she ignored the concerns of a panel of doctors and pharmacologists about the lack of scientific evidence of the vaccine’s long-term safety, that she ignored the stringent recommendations of the Formulary Executive Council (FEC) when she began the massive vaccination drive. The documents show that she ignored the FEC letter expressing concern: “Based on the available scientific evidence presented to the Council, there is still a need to establish long-term safety, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.”

The FEC recommended in its meeting and in a letter, that Dengvaxia should be introduced through small-scale pilot tests and phased implementation rather than across three regions in the country at the same time, “and only after a detailed “baseline” study of the prevalence and strains of dengue in the targeted area. The experts also recommended that Dengvaxia [should] be bought in small batches so the price could be negotiated down.” Furthermore, a DOH-commissioned economic evaluation report found the proposed price “not cost-effective.”

Independent Data Re-analysis Refutes Sanofi Safety Claims

Soon after Dengvaxia was licensed in six countries, a re-analysis of Sanofi’s clinical trial data by independent scientists from the Imperial College (London), Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and the University of Florida, was published in Science Magazine (2016)[9]. They reported that the vaccine’s effectiveness depends on the local epidemiology; its effect depends on how intense the local transmission of dengue is:

- “Vaccination in low-transmission settings may increase the incidence of more severe ‘secondary-like’ infection and, thus, the numbers hospitalized for dengue…

- In July 2015, long-term follow-up results for the third year of the trial showed that vaccinees in the youngest age group (2- to 5-year-olds) of the Asian trial had a substantially and significantly higher risk of hospitalization for virologically confirmed dengue disease than controls had.”

- Serological data were only collected from a subset of participants in each phase 3 trial, so it is not possible to determine whether the risk excess seen in the 2- to 5-year-old age group is driven by the effect of vaccine in the large proportion of seronegative recipients in this age group, but at present, this appears to be the most plausible explanation.

- The population-level impacts of vaccination hide enormous heterogeneity in benefits and risks at the level of the individual recipient. Seropositive recipients always gain a substantial benefit from vaccination (>90% reduction in the risk of being hospitalized with dengue), whereas seronegative recipients experience an increased risk of being hospitalized with dengue.

- This is true both in the short-term (see supplementary materials) and in the long-term and raises fundamental issues about individual versus population benefits of vaccination.

- Restricting the minimum licensed age of use of the vaccine to 9 years mitigates, but does not remove, the risk of negative population-level impacts in low-transmission settings where the majority of 9-year-olds are still seronegative.”

Another report in Science Magazine (2017), by a team of scientists at the University of California, Berkeley led by Professor Eva Harris analyzed more than 41,000 blood samples using different statistical approaches in search of a pattern that would explain why some children develop the severe form of the disease: “all roads led to Rome.” They report that all three methods identified a specific titer antibody that is predictive of severe disease. Children, whose antibodies from a previous infection fell to a certain low point, were eight times at higher risk of the deadly dengue infection.[10]

On November 29, 2017, Sanofi acknowledged that Dengvaxia increased the risk of severe dengue in children who were vaccinated:

“For those not previously infected by dengue virus, the analysis found that in the longer term, more cases of severe disease could occur following vaccination upon a subsequent dengue infection.”

By the time that Sanofi made that acknowledgment more than one million children – 830,000 in the Philippines and 300,000 in Brazil—had been exposed to the increased serious risk posed by the vaccine. That mass vaccination initiative was premature and a huge mistake, acknowledges Professor Neil Ferguson, an unpaid adviser to both Sanofi and the WHO: “The development process around the first dengue vaccine led to a degree of momentum and judgments that we should learn lessons from.”

Only after the Sanofi acknowledgment, in 2017, the WHO issued the following revised statement: “Following a consultation of the Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety, CYD-TDV (Dengvaxia) should not be administered to people who have not previously been infected with dengue virus.”

Volunteers Against Crime and Corruption in the Philippines received at least three deaths reports of children vaccinated with Dengvaxia; VACC requested the Justice Department to investigate the dengue vaccine deal.

On Dec. 5, 2017, the Philippine Daily Inquirer reported that Senator Dick Gordon, chair of the Senate blue ribbon committee, said that former President Aquino and former Health Secretary Garin could be held criminally liable for implementing a dengue immunization program that had been halted over safety concerns.

The Manilla Bulletin, reported on December 13, 2017, that Thomas Triomphe, Sanofi Pasteur Vice-President for Asia and Pacific, “apologized for his company’s issuance of a global advisory warning the public of the ill-effects of the vaccine if administered to persons who have not yet been infected with the deadly mosquito-borne virus.”

He then played linguistic calisthenics by claiming that “severe dengue” doesn’t mean severe illness…the terminology, he claimed, is “medical language” for “fever and bleeding gums”…

Representative Rodante Marcoleta rebuked Sanofi:

“You are very indifferent, [the] damage has already been done. You act as if you can casually play with the lives of the Filipino people, how can you be so inconsiderate.”

These insufferable maneuvers are clearly aimed at damage control in preparation for the looming Dengvaxia lawsuits.

Posted by Vera Sharav.

Read the full article at ahrp.org.

References:

[1] Clinical Efficacy and Safety of a Novel Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine in Healthy Children and Adolescents Aged 9 to 16 Years in Latin America, Villar L, Dayan GH, Arredondo-García JL, et al. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2015

[2] Development Of The Sanofi Pasteur Tetravalent Dengue Vaccine: One More Step Forward, Bruno Guy, Olivier Briand, Jean Lang, Melanie Saville, Nicholas Jackson, Vaccine, 2015

[3] Scientists Solve a Dengue Myster: Why Second Infection is Worse than First, Helen Branswell, STAT, Nov. 2017

[4] Did Sanofi, WHO Ignore Warning Signals on Dengue Vaccine? Julie Steenhuysen and Ben Hirschler, Reuters Health News, Dec. 12, 2017; Philippines Orders Probe Into Sanofi Dengue Vaccine for 730 Children, Manolo Serapio and Neil Morales, Reuters Business News, Dec. 3, 2017

[5] Philippines Eyes ‘Heightened Surveillance’ of Children Who Got Dengue Vaccine, ABS-CBN News, Dec. 11, 2017

[6] Dr. Halstead is currently Adjunct Professor at the Department of Preventive Medicine and Biometrics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. His recent articles: Dengue, Scott Halstead, MD the Lancet, 2007; Achieving Safe, Effective, And Durable Zika Virus Vaccines: Lessons From Dengue, The Lancet, 2017; The Impact of the Newly Licensed Dengue Vaccine in Endemic Countries, Maíra Aguiar, Nico Stollenwerk, Scott Halstead PLoS, 2016

[7] Sanofi Scandal in the Philippines Could Spread Dangerous Mistrust of Vaccines, Ed Silverman, STAT, Dec. 2017

[8] Garin ‘Ignored’ Experts’ Advice On Dengvaxia; No Testing Done To Find Out If Children Had Dengue Before Vaccination, By Tom Allard, Karen Lema, Reuters, Dec. 11, 2017

[9] Benefits and risks of the Sanofi-Pasteur Dengue Vaccine: Modeling Optimal Deployment, Neil Ferguson, Isabel Rodriguez-Barraquer, Ilaria Dorigatti, Luis Mier-y-Romero, Daniel Laydon, Derek Cummings, Science, 2016

[10] Antibody-Dependent Enhancement Of Severe Dengue Disease In Humans Leah Katzelnick, Lionel Gresh, Elizabeth Halloran, Juan Carlos Mercado, Guillemina Kuan, Aubree Gordon, Angel Balmasseda, Eva Harris, Science, 2017

Leave a Reply